Security Guidance

3 Governance and Documentation

3.1 Security Risk Management Policies

3.1.1 Mandate and Commitment

3.1.2 Approach to Security Risk Management

3.1.3 Security Responsibilities & Risk Owners

3.1.4 Creating Security in Depth

3.1.5 Operational Security Activities

3.1.6 Approaches to Security Education & Training

3.1.7 Reviews

3.2 Protective Procedures

3.3 Emergency Planning

4 Risk Management: Threat and Vulnerability

4.1 Asset Identification and Categorisation

4.2 Threat Identification and Evaluation

4.3 Risk Assessing

4.4 Vulnerability Assessments

6 Physical Security Considerations

6.1 Perimeter

6.2 Grounds

6.3 Walls and Building Fabric

6.4 External Doors

6.5 External Windows

6.6 Internal Physical Features

6.7 Stores

6.8 Secure Storage Facilities

6.9 Exhibiting and Display Cases

7.1 Intruder Detection System (IDS)

7.2 CCTV (Visual Surveillance) Systems

7.3 Access Control Systems (ACS)

7.4 Fire Alarm Systems (FAS)

7.5 Sprinkler System

8 Operational Security Considerations

8.1 Security Responsible People

8.2 Opening and Closing Activities

8.3 Access Control Activities

8.4 Collections Management Activities

8.5 Transportation of Collections / Loans

8.6 Search/Reading Room Activities

8.7 Fire Risk Management

8.8 Incident Reporting

1 Foreword

This security guidance document has been prepared for the Archives & Records Association – ARA (UK & Ireland) and its members. It will not answer all of the security questions that you may have but it will provide a solid basis upon which security risk management decisions can be taken. It should be read in conjunction with the guidance in relation to Archives Accreditation.

Due to the nature and type of organisations that are members of the ARA, the guidance has been written to apply to a wide range of venue types and in a manner that is sensible, proportionate, and easy to understand. Not all venues can afford specific physical or technical security systems, nor do they have additional human resources to devote to security so a balanced approach that is risk and resource-based must be offered.

This guidance aims to provide advice and guidance needed for members to make informed decisions about security risk management, how to use available resources and actions to consider to proactively protect their staff, users and assets. All organisations will have their own particular ways of working and there are different methodologies that can be applied to areas such as risk management. This document offers a particular approach but members should select and interpret the different sections with regard to their own circumstances.

The guidance aims to follow a logical sequence that will enable the reader to consider a wide range of issues that could adversely impact the security and integrity of archives and collections at their venues. To support ARA members Appendix 1 is a ‘Signpost Document’ designed to provide the reader with more detailed information and guidance if that is sought.

While written for the ARA many of the security measures described in this guidance are equally transferable to other cultural venues and sites whether holding archives or not. Wider stakeholders have been consulted as a part of this guidance development to ensure that it is not only accurate and timely, but that it is also aligned, as far as possible, with future legislation and international good practices.

The guidance was developed by Trident Manor Ltd. with input from the ARA Security & Access Group and others with relevant expertise. This guidance will be subject to periodic reviews and updated by the ARA Security & Access Group as required. Thanks are due to the SAG group and to Andy Davis of Trident Manor for producing the documentation. We are also grateful to The National Archives for funding this important project.

2 What is Security?

Before starting to write guidance and advice about ‘Security’ it is appropriate to understand what ‘security’ in the context of this document is. Security is defined as “The condition of being protected from loss, harm, or damage.”[1]

What is important to recognise is that ‘security’ doesn’t just happen! To create the ‘condition’ positive actions have to be taken that support the achievement of ‘protection’ and these normally require the implementation of security measures which can be physical, technical, operational, or educational.

Good security is a continuous and proactive activity that should be practised by everybody within an organisation and be everybody’s responsibility.

[1] ASIS International, Risk Assessing Standards, 2016

3 Governance and Documentation

The development of governance and documentation helps organisations to manage security threats, risks, and vulnerabilities, and to record the decisions that have been made. It is important to ensure that everybody within an organisation understands what is expected, who is responsible for protective security, and how it is expected to be implemented.

The size and style of security governance will be dictated by the complexity of the operations, the nature and structure of the organisation, the threats that are faced, and the risks those threats pose.

Any security documentation that is created should be in a style that can be easily understood, not too technical, and is pragmatic. The overcomplication of any documentation will result in it either not being read, or worse, not being understood by those who are expected to deliver and use it to protect people and assets.

“Assets” can be understood as collections, records, buildings or equipment – anything that the archive identifies as needing protection. It is often helpful to state upfront that the protection of living people always takes precedence over the protection of assets.

Generally, security governance and documentation will fall into the following categories:

Security Risk Management Policies

Protective Procedures

Emergency Planning

A critical point with any security documents which in themselves can provide information which would be of value to adversaries is that they must be protected and only circulated on a restricted basis. For example, not everybody needs to know and understand how the documentation of archives works, nor do they need access. Information should be shared on a ‘Need to Know-Need to Access Basis’.

Where appropriate, governance and documentary materials should be categorised in accordance with their sensitivity and restrictions applied accordingly (e.g. storing them in an area of the network with limited access). This will reduce the risk of accidental and intentional disclosure of sensitive materials.

3.1 Security Risk Management Policies

An organisation’s security risk management policy will outline the rules, expectations, and approaches that are to be taken to protect the organisation's assets from loss, harm, or damage. It is directional and can come in many formats such as a stand-alone document or as part of a wider organisational policy. An organisation may deem that particular documentation is unnecessary, but this is a risk management decision itself.

Best practice recommends that a security risk management policy is established to avoid confusion and to ensure the protection of assets takes place in an expected manner. From a legal perspective, it also means that a defendable approach is developed upon which actions can be assessed, as opposed to an inference being made because of the lack of a policy or protective direction.

Any security risk management policy should be based upon realistic risks that exist or can be expected to impact the organisation and its assets, now or in the future. Where possible the policy should be specific to the archive, library, or collection, even when the venue/operation may be a part of a wider organisation. To confirm the policy’s importance, it should be approved by the most appropriate person, preferably the risk owner or other senior responsible person.

This guidance document is not prescriptive, as long as any policy created contains relevant information to protect the organisation's assets then it is appropriate. However, careful consideration needs to be taken to ensure that all security risks that exist are covered either within this or another policy. If separate there should be some cross-referencing to ensure that risks have been captured and considered.

Examples of other standard policies which should intersect with Security policy include:

Health and Safety Policy

Information Security Policy

Collections Management Policy

Preservation Policy

A Security Risk Management Policy should provide the direction for the organisation to follow and should/can include the following non-exhaustive areas:

Organisational mandate and commitment

Approach to security risks

Security responsibilities & risk owners

Creating security in depth

Operational security activities

Approaches to security education and training

Process for review of policies, procedures and incidents

3.1.1 Mandate and Commitment

This sends a message to the organisation that the Leadership Team has bought into the Security Risk Management Policy and is committed to supporting it. It highlights key areas that have been considered important for the protection of the organisation and its assets. It is possible to have the mandate and commitment shown as a separate document (Example 1) similar to a Health & Safety Policy Statement

EXAMPLE 1

Security Policy Statement – Mandate & Commitment

The Senior Leadership Team (SLT) is committed to supporting, resourcing, and providing the strategic direction needed to protect all organisational assets. All staff are responsible for proactively reducing the security risks that exist or are anticipated. The policy will:

Provide a framework that enables security risk management activities to take place in a consistent, sustained, and controlled manner.

Clearly define what organisational security responsibilities exist, and at which level.

Help reduce the risks to personal safety and security of staff, contractors, and visitors to the organisation.

Reduce the risk of assets being lost, stolen, damaged or degraded.

Improve the protection of information and data.

Help develop a proactive security culture.

Optimise the efficiency of security operations.

Increase the robustness of the organisation’s security approach and minimise the security threats that exist.

The SLT acknowledges the importance of integrating security measures and strategies, (human, technical and physical) to ensure cost-effectiveness and appropriately layered systems. Our approach to security risk management focuses on preventing incidents as well as enhancing the capacity to respond effectively to them when they occur.

A. N. Other

Chair of Organisation 31st July 2023

In doing so the key areas and commitments of the Leadership Team can be highlighted, and the ‘Security Policy Statement’ be displayed in a manner that will increase the likelihood of it being read and understood by staff.

3.1.2 Approach to Security Risk Management

This part of the policy is a high-level directive and not a risk assessment of the organisation or its assets.

This may be part of a wider organisational risk management policy but should include the specific security risks which archives, libraries, and collections have to consider outside a more general cross-organisational approach.

All organisations should seek to manage and reduce security risks, ‘As Low as Reasonably Practicable’ with the important part being the word ‘Practicable’. Practicable means that security measures, treatments, or acceptance should be such that they do not adversely impact the operational capabilities, financial constraints, or the reputation of the organisation.

No organisation can remove all the risks that exist, many members of the ARA may not have the financial or personnel resources to do so, but all organisations can seek to manage them.

The policy should outline the risk management approach that will be taken to:

Identify the threats.

Understand the risks the threats pose.

Identify security vulnerabilities.

Appropriately treat and manage risks.

Where a Risk Management Policy is cross-organisational the approach may already exist, if so, the security risk management policy should link to or derive from this. (See Tip 1) By adopting this approach the specific risks facing archives, libraries, or collections are being captured and considered.

TIP 1

Where an organisational risk management policy already exists add the security risk management policy as an Appendix. If an organisational security risk management (SRM) policy already exists consider adding the archive, library, or collection SRM policy as an Appendix to that larger one.

Where documents and templates are available to support the risk management approach used, they should be attached as an Appendix to any policy.

3.1.3 Security Responsibilities & Risk Owners

The policy should identify who is the organisational/departmental lead on security. In larger organisations, the Leadership Team may delegate this to an appropriate named individual. They should be identified as should anybody with a specific remit around security. The ‘Risk Owners’ will normally be the Leadership Team and the fact that they delegate security responsibilities does not normally absolve them of risk ownership. In smaller organisations, the security responsible person could have multiple roles and responsibilities while also being the ‘Risk Owner’.

Security responsibilities and risk ownership will often be dictated by the shape, size, and characteristics of the organisation and the assets being held. The larger the organisation the more likely that security professionals will be employed and that a greater need for cross-departmental working will be required.

TIP 2

When there are multiple departments within an organisation it is sometimes better to have a ‘Security Committee’ where representatives from different departments can come together to discuss and agree security policy implementations. This way silos are broken down and everybody can add their point of view to any discussion. This demonstrates inclusivity and reduces the likelihood of unintentional oversights or omissions occurring.

All organisations should consider oversight of the risk owners’ activities either by committee or external independent audit processes.

Any policy should be a tool for the development and progression of a positive security culture within any organisation, it should highlight that it is everybody’s responsibility to protect organisational assets. Clearly defined job descriptions are a great tool to achieve this and help start the development of the security culture.

3.1.4 Creating Security in Depth

Creating Security in Depth is covered in greater detail in Part 5 of this guidance, but it is beneficial for the policy document to provide the direction that the organisation takes with regard to security programme design. It should articulate that single levels of security should be avoided as far as possible and each layer that is added should support other measures to increase the overall protective robustness.

The policy should clearly define any standards that are being adopted, such as LPS1175 for physical security standards[1] and BS 8243 for intruder detection systems. It should also include any guidance that is required to meet regulatory requirements such as Annex E for ‘Transportation Guidance’ when lending under the Government Indemnity Scheme.[2]

[1] https://www.redbooklive.com/download/pdf/LPS1175.pdf

[2] https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/supporting-arts-museums-and-libraries/supporting-collections-and-cultural-property/government-indemnity-scheme

Security in depth is created by applying multiple layers of protective measures so that a robust protective programme is created. Relying on a single layer of security means that a criminal or adversary only has to bypass one layer of protection before they reach an organisation’s assets. Therefore, this should be clearly defined in the policy. (See Example 2)

EXAMPLE 2

Creating Security in Depth

The Senior Leadership Team (SLT) recognises that the most robust protective security is created by adopting a multi-layered approach to the protection of the organisation’s assets. Single layers of security should be avoided wherever possible and practicable.

We identify security measures as consisting of the following types:

Physical security measures

Technical security measures

Operational security practices

Continuous security training and education

The purpose of ‘security in depth’ is to support the principles of:

Deter Makes the venue/organisation unattractive to adversarial threats.

Detect Spots potentially illegal activities and initiate a form of response.

Delay Slows down any adversarial attack using the above security measures.

Respond Enables a timely response before any attack is completed.

By adopting this approach, security risk management subjectivity should be greatly reduced.

3.1.5 Operational Security Activities

This part of the policy should address behavioural aspects of the organisation's approach to security risk management. It can include the security profile that the Leadership Team expect to be taken, including a reaffirmation of the fact that the protection of the organisational assets is everybody’s responsibility. All security operations should be risk-based.

TIP 3

Do not include practices and procedures in the main body of a security policy, reference them and add them as an Appendix to the policy. In doing so the flow of the Policy (a strategic document) is not interrupted by detailed operational practices (which are likely to need to be updated more frequently than the policy itself).

The policy document should highlight the need for continued awareness and vigilance by all staff and that practices and procedures[1] exist to help protect the organisation’s staff, users and assets. The nature and characteristics of the organisation will dictate how detailed they need to be.

Where necessary, and subject to the requirements, reference can be drawn to key operational activities undertaken at or by the organisation. (Example 3)

EXAMPLE 3

Operational Security – Procedures

To help deliver this policy, Operational Procedures and Practices exist to ensure that a structured approach is taken to protect the organisational assets. These procedures are specific to (Venue) which is a part of (##) Organisation.

There are situations where the procedures cross different departmental working practices. Where this occurs the lead department will be identified, and they are to ensure that broader cross-departmental engagement takes place to minimise risks.

A complete list of Operational Security Practices/Procedures can be found in Appendix ‘XX’ of this policy, the following are viewed as key activities:

Opening and Closing Procedures

Access Control Procedures

Personal Safety & Security Procedures

Search/Reading room Protocols (Collaborative protective security activity)

Access to Collections (Collaborative protective security activity)

Security Transportation of Documents

Exhibition Security Procedures

Lockdown/Evacuation Procedures

Reader Admission Procedure

Exhibition Loans Procedure

Record keeping and documentation

Disaster Response and Recovery

3.1.6 Approaches to Security Education and Training

Security does not just happen. To ensure its effectiveness, people should be educated about the organisational approach to security and the protection of assets. The policy should stress the importance of security education and training equally as much as physical and operational security measures; you can have all the security in the world but this will fail if staff are not educated on the following:

What exists.

Why it exists.

What individuals are to do.

AND

How to do it.

There is a risk that time, money, and effort may be wasted, security measures may not be implemented or gaps may be created, simply because effective training did not take place.

The policy should outline the support for continual security learning and development from induction through to attending specialist programmes, as necessary. This again will be dictated by organisational size, nature, and budget.

EXAMPLE 4

Review/Frequency

Annual report Frequency: Annually (subject to size and nature of the organisation)

Policy Frequency: Annually

Practices & procedures Frequency: Biannually (or after a major incident)

Threat, risk and vulnerability assessments/risk registers Frequency: Annually - subject to risk (or following a major incident)

Security training Frequency: On recruitment, quarterly, continuously

Security job description Frequency: Annually

These reviews should form part of the security risk management Annual Report prepared for an organisation to ensure compliance with any policy that exists and demonstrate best practise. External audit reviews are also beneficial in providing additional scrutiny and perspective.

3.2 Protective Procedures

While the ‘Policy’ provides the strategic direction, practices and procedures provide the operational instructions to support the protection of organisational assets. From an organisational perspective an (operational) ‘procedure’ is defined as, “A set of step-by-step instructions compiled by an organization to help workers carry out routine operations.”

The term Protective Procedures is used instead of ‘Security Procedures’ because many procedures are not definable as ‘security’, but most can be seen to add a protective value to the safeguarding of organisational assets and individuals.

Many organisational activities and procedures may rest with different departments or individuals who may have nothing to do with a defined security role or function. (Within the broader cultural community this is more often the case.)

Where security personnel are used at venues, they will normally be given a set of SOPs (Standard Operating Procedures) or Assignment Instructions (AI). These define how they will carry out their security duties while at work. These instructions should be checked and verified to ensure that they meet the organisational needs and do not accept unnecessary liability.

As with all documentary governance, there is no need to overcomplicate things and any procedure should be of a size that will include the necessary information but not be so long as to discourage individuals from reading it. In an ideal world a ‘procedure on a page’ would be great, however, many operational activities are rather more complicated.

The format and structure of any procedure is often dictated by wider organisational approaches. However, a standardised format helps the reader understand the sequence of processes and is therefore sometimes easier to follow.

TIP 4

As far as possible maintain a standardised format to all procedures within an organisation or department.

There are some procedures that all organisations, irrespective of size, contents, and personnel should possess and others can be added based on the operational context, value, and wider organisational requirements. Example 3 above highlights some of the more common procedures that would be expected in ARA members’ venues.

3.3 Emergency Planning

Emergency planning is a critical element of all cultural venues’ protective governance. Fire will always be one of the main threats that archives and libraries will face because of the capacity for damage to contents. However, other emergency planning scenarios need to be considered.

Each organisation should maintain emergency plans in an acceptable format that can be easily reviewed, actioned, and updated as necessary. Consideration should be given to having paper copies in a defined secure location as well as online files, so that relevant information can be readily accessed in the event of an emergency, e.g. a power outage. As with all governance, it is the content that is critical and not the size of the plan.

Sometimes it is helpful to distinguish between what is an emergency and what would be classed as a crisis.

An emergency is defined as, “something dangerous or serious, such as an accident, that happens suddenly or unexpectedly and needs fast action to avoid harmful results.” [1]

A crisis is defined as, “a situation that significantly falls outside normal business operations, and which has the ability to severely impact continued operations and its financial well-being.”

Additional crisis characteristics include:

Unexpected, immediate exposure to significant threats, violence, or damage situations – whether perceived or actual.

Significant media interest that needs to be proactively addressed and managed to maintain reputational trust and support. (Regional, national, and international)

In this guidance ‘significant’ means where the event is of a sufficient size and nature to be worthy of immediate attention and where long-term effects, survivability or adverse impacts on the organisation have the potential to occur. Then it would normally be defined as a crisis.

A ‘crisis’ is normally something that has the potential to impact at the corporate level and normally requires a strategic response and can be seen as an escalation from an incident to an emergency, and then onto a crisis. (Image 1)

[1] https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/emergency

Image 1 – Crisis Escalation Progression

While Image 1 shows a process not all incidents follow the same pattern, and the nature of the incident could categorise it as an emergency or crisis straight away.

It is always helpful for organisations to know and understand what type of events require certain responses so that appropriate resources are allocated, and subjectivity reduced.

TIP 5

As an organisation, agree and identify the type of events that would be dealt with through:

Incident management

Emergency response

Crisis management

The important thing is not the title, size, or type of document produced, it is the content and everybody’s understanding of what is to be done and by whom.

Where relevant the following (non-exhaustive) may feature within an organisation’s Emergency Planning considerations:

EXAMPLE 5

Emergency Planning Considerations

Fire Plan

Water ingress response

Salvage Plan

Loss of utilities

Injuries or death at the venue

Major loss/theft of documents

Data breach

Health and Safety violation

Act of terrorism

Protester/activism

Significant financial event

Significant environmental incident

Industrial action

Emergency planning should be organisation and site-specific. It should be based on the realistic risks that exist from natural and adversarial threat sources and it should be fully understood by everybody who is expected to play a part in the plan’s implementation. The plans should be tested and reviewed at least annually unless a significant event has taken place that has led to the implementation of the plan (which should then be reviewed to assess how well it actually worked).

4 Risk Management Threat and Vulnerability

Any security strategies, advice, or guidance should be risk-based to ensure that efforts are targeted towards the threats that can cause the most harm, especially where weaknesses exist and can be exploited. While there are software packages available to help with this process anybody can do it by adopting simple processes.

This section will outline key considerations including the following:

What needs protecting? (People / Assets)

What can harm them? (Threats)

The likelihood and impact of loss, harm, or damage. (Risks)

Where gaps exist that can be exploited by threats. (Vulnerabilities)

Image 2 – Process of Managing Risks

A Threat is defined as, “A potential cause of an unwanted incident which may result in harm to individuals, assets, a system or organization, the environment, or the community” [1] The important thing to note is that a threat is the ‘cause’ of the potential loss, harm, or damage, while a risk is the ‘effect’ caused by assessing the likelihood against the consequences/impact of the threat occurring.

Many people confuse threat with risk and believe that they are interchangeable, they are not, Threat = Cause, Risk = Effect.

A vulnerability is defined as, “The conditions determined by physical, social, economic and environmental factors or processes which increase the susceptibility of an individual, a community, assets or systems to the impacts of hazards.” In a security context, a vulnerability is something that can be exploited by a threat.

To support the risk assessing process a document containing risk management descriptors has been included at Appendix 2 of this guidance.

[1] ASIS/RIMS – Risk Assessment Standard - 2015

4.1 Asset[1] Identification and Categorisation

Before undertaking any threat, risk, or vulnerability assessment it is important to know and understand what you want to protect. People naturally take priority. By categorising assets such as collections, buildings or equipment (e.g. as Critical, Important or Ancillary) you get a greater understanding of where protective resources need to be focused. The less critical an asset, the lower the effort needed to protect it, unless by breaching it a greater risk is created for a more critical asset. (See Appendix 2 for a supporting table that can be used.)

This method of asset categorisation can equally apply to existing asset registers or to new ones created using Excel or bespoke asset management software programmes. Effective registers have been seen that are as simple as having a page for each of the asset ratings.

In its most basic form, an asset register that contains the name of the asset, location, and criticality (alongside any special instructions) is all that is needed to help during the risk assessment process especially when considering the proportionality of measures.

By understanding what assets exist, where they are, and their criticality to the organisation, any threat evaluation, and the risk they pose will be contextualised alongside any vulnerabilities that are found.

[1]Best practice would dictate that an organisation has an asset register but that is not always the case. From a protective perspective it is normally appropriate to list assets that can or do have a direct impact on operational activities. It will be down to the venue to agree what assets are recorded and where, equally it may be that this relates to archives or collections only.

4.2 Threat Identification and Evaluation

When organisations look at threat sources from a ‘security’ context they primarily look at the criminal threat. However, as shown in the definition there is no reference to crime; it only talks about protecting from loss, harm, or damage. When considering the threats that can impact an organisation it is better to look much wider.[1]

To make an assessment truly effective it is better to be specific rather than just looking at the ‘general’ threat source. While assessing ‘general’ threat sources such as ‘crime’ there are too many variables which if not examined closer could result in inappropriate protective measures being applied or vulnerabilities created. By considering specific threats a greater accuracy in the overall assessment process will be achieved.

[1] There can be cross-over with health and safety and other legislation providing they have been identified and assessed during a process that is acceptable.

EXAMPLE 6

General Threat

Specific Threat

General Threat: Crime

Burglary

Organised crime

Insider threat

Fraud

General Threat: Social

Drugs

Anti-social behaviour

Industrial actions

General Threat: Environmental

Flooding

Wildfire

Landslides

General Threat: Medical

COVID

Avian flu

Norovirus

General Threat: Infrastructure

Loss of IT

Failure of environmental controls (e.g. air conditioning)

Water contamination

Power outages

General Threat: Terrorism

Marauding attack (firearms or bladed/blunt force weapons)

Vehicle as weapon

Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs)

Fire as a weapon

Chemical, biological and radiological (CBR)

Cyber

General Threat: Other

Human error

Information disclosure

When assessing threats, it is important to consider realistic threats that have, can, and could impact on the venue, collections and archives. Not all threats will be relevant.

By considering the assets being held a list of different threat sources can be prepared to enable the risks they pose to be assessed.

4.3 Risk Assessing

Risk management is an identified business discipline, and organisations should have a Risk Management Policy and a Risk Register (sometimes associated with the Asset Register), though unfortunately not all do.

This guidance will outline a basic risk assessing process that can be followed by all. Some venues may have the luxury of risk management software, however, that does not and should not negate organisations undertaking a risk assessment process or at least stress testing any software programme's findings.

Where possible it is always recommended that a collaborative approach is taken to risk assessing as it reduces the likelihood of unintentional biases creeping in and not being challenged.

Any risk assessment must consider the organisation's risk appetite and tolerance levels and one of the easiest ways of achieving this and avoiding subjectivity is to use a process that is cross-organisational and based on clearly defined descriptors that have been agreed and approved by the leadership team. (See Appendix 2 for examples that can be used.)

Most processes are based on numerical descriptors often associated with a colour that supports the numerical allocation. This process should be adopted for the likelihood of the threat and the consequences of it occurring. An overall risk score is generated by multiplying the likelihood score by the consequences score. Subject to the organisation a different number of ratings can be applied (3= Low, Moderate, High, through to 7 which becomes too complex for many.)

TIP 6

Using 5 x 5 ratings allows greater accuracy (than just using 3) in the evaluation and remains relatively easy to follow (as opposed to 7).

Appendix 2 demonstrates the use of colours to help identify and highlight where priorities are when it comes to the risk treatments. A venue may contain items that are not attractive to criminals so the threat from criminals may be viewed as low or very low. However, if the venue contained special collections and materials that had a high value and were attractive to criminals the risk scores would differ and be much higher. (See Example 7)

EXAMPLE 7

A local authority archive contains three stacks of paper-based social history materials (assets) that have little financial value and would not be attractive to criminals.

The likelihood of both theft and arson (intentional damage by fire) is scored as 2 (Low), however the consequences of arson are scored higher than theft at 5 (Critical). Therefore, the risk of theft-related threats is Low (2x3=6) however the risk posed by arson is higher (2x5=10) which using the scoring matrix increases the risk to Moderate.

There are of course other kinds of value than monetary value and this is where it is essential that archives understand their holdings and their cultural, social and evidential value which could expose them to different kinds of risk.

A point to note regarding the risk posed by the terrorist threat, especially in the context of ARA members, while the assessed likelihood may be low or very low, the consequences will always be critical due to the increased likelihood of loss of life. Therefore, risk mitigation measures must always be considered.

TIP 7

It is also important to consider ‘risk transference’ from any neighbouring or adjoining businesses and organisations. Are they at a greater risk of any particular threat, organised crime, terrorism, or protesters? If so your score should consider and reflect that.

The above is a basic approach to risk assessing that all organisations and ARA members can take. However, the risk assessing process can go a stage further and identify ‘risk mitigations’ followed by a re-evaluation of the scores. Effective risk treatments should reduce the final risk rating, but that is not always the case and sometimes the final risk score cannot be changed, they are already “as low as reasonably practicable”.

The risk assessment can be desk-based but is better being done as both a documentary review and a site visit. During the site visit, it is often possible to incorporate the risk re-evaluation with the undertaking of a vulnerability assessment. This not only helps contextualise the threats and the risks that exist but also assess existing protective measures while looking for vulnerabilities.

4.4 Vulnerability Assessments

A vulnerability assessment is the identification, categorisation, and prioritisation of weaknesses that can impact the integrity of an organisation's assets and seek ways to reduce or manage them.

One of the easiest ways to identify vulnerabilities is to reverse mindset, i.e. think like the threat source. When looking at adversarial threats it can help to put yourself in the position of the adversary so you can ask yourself the question, “If I was going to attack this place (criminal, terrorist, or protester) how would I do it?”

When adopting this approach, it is always better to start where the adversary would start, outside the building and grounds, before working your way into the most secure part of the building/venue, which hopefully an intruder will not be able to access.

This is where understanding the threats and the level of risk that they pose is important as it can be contextualised so that realistic considerations are made, and the assessment does not head off into some fantasy world as depicted by Hollywood blockbusters.

It is also sometimes beneficial to identify the type of vulnerability whether physical, operational, technical, or educational, which corresponds with the types of (non-IT) protective security measures that exist. This can help when considering solutions to address the vulnerabilities.

It is sometimes easier to create a simple vulnerability assessment spreadsheet where vulnerabilities that are identified can be recorded and then evaluated for the level of harm they pose to the assets (subject to the asset criticality). That way a record that can be cross-referenced against other documents can be made and vulnerabilities are not forgotten.

Once vulnerabilities have been identified and recorded you can then switch mental roles and start to ‘TlaD’ (Think like a Defender), asking “How can I address these vulnerabilities to reduce or prevent the risk we face.” In 90% of cases, non-experts can identify sensible solutions. Sometimes professional help and assistance may be required to identify the vulnerabilities and then understand the best way of reducing and managing them, so risks are lowered.

Remember not all vulnerabilities have to be addressed or can be addressed. Sometimes if the risk posed by the threat and the vulnerability does not impact any important or critical assets then the risk/vulnerability can be accepted.

If accepted it should be recorded in either the vulnerability or risk assessment documentation to show that it was not an oversight, it was an informed decision.

5 Creating Security in Depth

The best way to secure any venue and its contents is to create multiple layers of security consisting of physical, technical, operational, and educational security measures that collectively offer robust and resilient layers of protection. It is always better to overarch and interlock security measures so that they always support the efforts of another, and you are not faced with a situation where there are no or limited lines of security.

Image 3 – Protective layered security

Where there are only single layers of protection there will always be vulnerabilities that once exploited can result in the loss of assets. Therefore, when you have critical assets, they should always be behind multiple protective layers and preferably away from external walls or access points. The goal is to achieve the red area in Image 3.

As outlined earlier the purpose of security in depth is to create a situation where an adversary is deterred, detected, or delayed, and a response is generated before loss or harm occur.

Image 4 – DDDR principles

EXAMPLE 8

Deter: If by appearance alone somebody sees robust physical barriers, technical systems such as CCTV and Intruder Detection Systems (IDS), and effective search and patrolling activities, the likelihood of the adversary being deterred is increased and risks are reduced.

Detect: If there are CCTV systems that are being proactively monitored, motion sensors correctly positioned around the building, and an electronic access control system delineating public and private spaces there is a greater likelihood of detecting any adversarial activities (day/night) and a timelier response generated if they haven’t already been deterred.

Delay: Using a perimeter fence, the installation of robust doors, shutters and other physical barriers can delay an adversary reaching the intended target or critical assets, as can effective operational practices. These may prevent an attack from continuing and allow a timelier response, when supported by technical systems and effective operations.

Respond: The response is normally generated by the activation (detection) of the technical system. The more effective the system the sooner the response (staff, security, or police). From initial notification until arrival at the scene the physical measures should provide an adequate delay during an attack that minimises the loss, harm, or damage caused to the organisational assets.

As can be seen from the above example the protective layers are mutually supportive and work to protect the organisation’s assets. Due to the nature of archives, libraries, and other cultural venues, there is a need for the public and other third parties to have access and engagement with venues and their collections. That does not mean that the above principles and approach cannot be used, it is just that adjustments are to be made and different day/night strategies adopted.

The creation of effective security in depth should be a considered action. It should be based on realistic threats that exist or can be expected, it should consider the risk those threats pose, and it should faction in any vulnerabilities or areas of likely adversarial exploitation. Effective security in depth should make it harder for adversaries to be successful and reduce the risks being faced by venues.

As with all aspects of security it does not just happen and careful considerations must be made about balancing the robustness with the need to function as a venue, the type of measures used, cost, and overall benefits to the organisation. Planning, discussing, and agreeing on any security design is always appropriate and can reduce the risks of ineffective security designs and layers being introduced. Once designed, consider and test the effectiveness before proceeding with any new installations. Just because you have five layers of protection it does not mean assets are protected and vulnerabilities could have been created. (Image 5)

Image 5 – Effective layered security

The size, nature, and value of the archive and collection might be such that professional security advice and guidance is needed, whether internally or externally. Preference should always be given to professionals who know and understand the cultural sector, and in particular archives, libraries, and dealing with special collections, not because they have superior technical knowledge but because they have a better understanding of the context in which security and operational matters need to harmonise.

It may not always be possible to implement certain types of security measures so there may be a need to double or triple up on other available options. This should not be used as a means of seeking a quick fix or cutting costs as this can increase risks and vulnerabilities, but it is an option providing the overall robustness and resilience is not compromised.

Introducing effective security in depth requires some knowledge of physical, technical, operational, and educational security measures. The following sections of this guidance will help increase their level of knowledge and make informed decisions about what is needed and best for their venues.

6 Physical Security Considerations

Physical security is defined as “That part of security concerned with physical measures designed to safeguard people, to prevent unauthorised access to equipment, facilities, material, and documents; and to safeguard them against a security incident.”

Good physical security is the cornerstone of effective protection of assets and as described above provides that delay while a response is mounted or may prove so effective that the attack is abandoned.

Effective physical security does not mean that there is a need to create a fortress that is uninviting to visitors, but it does mean that effective measures are considered based on the threats that exist and the risk they pose.

It is always far easier and better if physical security measures are designed into a venue rather than retrofitting them (the same is true for technical systems), it is also normally more cost-effective.

As far as possible try to have security expertise working with the architects and project design team, especially if seeking coverage under the GIS (Government Indemnity Scheme). Police forces across the United Kingdom have DOCOs (Designing Out Crime Officers) and CTSAs (Counter Terrorism Security Advisers) from the Counter Terrorism Police (CTP) provide advice and guidance throughout the building design stages and can be an invaluable resource. However, they may not have the necessary experience of working within cultural settings and therefore advice and guidance from other sources may still be needed.

The same is true when considering introducing physical security measures into buildings that are ‘Listed.’ There are strict controls on what can be done at this type of property and professional guidance should be sought at the earliest opportunity so that time is not wasted considering a security measure that will never be accepted.

TIP 8

Identify and engage with the local planning department at the earliest opportunity. Outline what you would like to achieve and explain the reasons why. The more you can justify that your proposals have been carefully considered the more likely approval can be granted. Consider it a collaboration and listen to what they say, compromises on both sides may be needed. They are not your enemy!

Where a property is listed never proceed without written permission being granted by the planning department as fines, the need to make good, and reputational damage can have a serious impact. Once permissions have been granted then effective physical security measures can be introduced.

When higher-grade physical security requirements are being considered these should be considered using appropriate standards that provide an adequate delay based on an attack using different types of tools. Some standards do not use appropriate testing methods and can result in unintentional vulnerabilities.

The testing undertaken by the Loss Prevention Certification Board and outlined in the Loss Prevention Standard LPS1175 is the most widely accepted within the cultural community and frequently used by Consultants from Arts Council England. However, other testing standards do exist, and physical security products tested by the National Protective Security Authority[1] (NPSA - formerly CPNI) and Secured by Design can be viewed as appropriate.

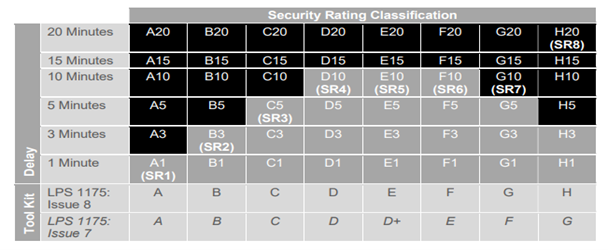

LPS1175 is the preferred standard due to the comprehensiveness of its testing processes relating to intruder resistance and physical security products, which is measured by the penetration delay achieved by the product, and not the total attack time which may be much longer. (Table 1)

Table 1 – Extract from LPS1175: Issue 8.1[1]

[1] BRE Global Ltd. https://www.redbooklive.com/download/pdf/LPS1175.pdf

Different toolsets are used during the testing during the LPS1175 testing process which can be found on pages 28-34 of https://www.redbooklive.com/download/pdf/LPS1175.pdf.

When considering what physical security measures to implement it is often easier to work from the outside up to the most protected areas and thinking like a criminal (as with the vulnerability assessments).

When there is no in-house expertise then professional help should be sought from the police, professional security bodies, or trusted security professionals.

Where relevant the following areas should be considered for physical security enhancements.

6.1 Perimeter

A perimeter is defined as, “the outer edge of an area of land or the border around it”[1] and in a protective context identifies the outer line of control between public and private spaces. However, it is not always that easy as there may be a ‘perimeter’ at night but not during the day when the public have a right of access.

There may also be a boundary but no physical feature or one where natural topography has been used instead of a man-made structure. No two venues are the same and informed decisions need to be made based on the individual circumstances that exist. This could include not enforcing any perimeter controls and allowing everything up to the venue's curtilage to be surrenderable.

It has to be remembered that even fortresses have access points and as such breaches in the perimeter. These are often seen as a vulnerable point and any protection should be at the same level as the perimeter.

From a security risk management perspective, a clearly defined perimeter is a practical way of starting the ‘security in depth’ process. The threats/risks that exist will influence what is needed, budgets will influence what can be afforded, and aesthetics will need to be considered to ensure customer and internal acceptance.

Where a higher level of security is considered appropriate for any fence then the access points in that fence should offer an equal level of protection unless personnel are deployed at that location.

Appendix 3 identifies some of the more common perimeter types with advantages and disadvantages associated with each. Further advice and guidance can be found in BS EN 16893: 2018 Section 5.1 Building Location.

[1] https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/perimeter

6.2 Grounds

An area that is often forgotten about when considering protective security is the grounds between the perimeter/boundary and the fabric of the venue. The area immediately surrounding buildings is referred to as the curtilage and may or may not form a part of the venue’s footprint.

The grounds are an important part of a building’s security and can directly impact the target attractiveness of a venue, or act as a deterrent. Wherever possible the grounds should be maintained to improve the natural surveillance for individuals using and protecting the space. Maintaining sterile areas where the space between the perimeter and the building fabric is effective, but normally unachievable. The proximity of any vegetation to the outside of the building should be reviewed, does it create an area of concealment where they could attack people or the building itself? If so, consider whether it is necessary or could be better positioned elsewhere.

External lighting plays an important part in the protection of assets as it supports the surveillance effort of security personnel and minimises the likelihood of criminals being able to conceal themselves. It also provides a positive reinforcement of operational effectiveness while allowing secondary surveillance to be undertaken by others. The use of motion sensor lighting is a positive measure and more cost-effective than continuous lighting or lighting on a timer at dusk and dawn.

Where possible the grounds should be considered during any security design stages so that areas of concealment are reduced, choke points created where individuals are funnelled, and clear lines of sight achievable by people and technology. The grounds should be considered during the security in depth process as it can work towards the Deter, Detect, Delay (through open space), and enable a response to be generated.

When there is little control of the grounds surrounding the venue (i.e. public footpaths, parks etc.) consider the ‘curtilage’ and areas that are in your control. As far as possible maintain and keep the area free from rubbish (highlights orderly behaviour and effective operations), avoid allowing anything to be secured or fastened to the fabric of the building, and make sure there is nothing so close that would allow easy access to spaces above the ground floor.

TIP 9

Keep rubbish bins locked away until the day of them being emptied. Doing so may reduce the risk of them being used to access areas above the ground floor.

As far as possible, check the whole of the grounds and the venue’s curtilage, looking for vulnerabilities which should include considering if a ‘ram-raid’ style attack is possible and whether physical features could be added that would reduce this risk.

Often archives, libraries and other venues used by ARA members are co-located with other departments or businesses without a degree of exclusivity to the grounds or spaces immediately outside their area of operation or control. That should not prevent the security risks from being considered and concerns (if identified) raised with the relevant controller of the space, preventing crimes, and reducing risks should be welcomed.

6.3 Walls and Building Fabric

Building designs have changed radically over recent times moving from more traditional brick buildings in the older buildings through to glazed curtain-walled designs in the more modern ones. Older buildings had thick walls which would require more effort to breach than modern blockwork or glazed walling.

The appearance, fabric, and condition of the external building walls will all have an impact on an adversarial mindset and any consideration they may have about the ease of ingress.

The use of modern products including blockwork and glass does not provide the robustness that traditional stone and brick walls do, and they may be identified as a vulnerability. It should also be remembered that glazing allows in light and ultraviolet/infrared (UV/IR) radiation which can damage archives, libraries, and collections. Where this type of walling exists consider the application of film on the inner face of the glazed curtain walling. This can help reduce the UV/IR risk, delay illegal entry, or reduce glass fragmentation subject to the type and thickness of the film used.

As far as possible, high-value collections or stores should not be in rooms directly accessible via an external wall. Where this is unavoidable then steps should be taken to confirm the exact composition of the wall and if necessary, increase its robustness by reinforcing the inner face[1] using modular walling systems, expanded metal materials, or other materials that will cause a delay. This can include externally added materials, although attacking these defensive measures becomes much easier as they are exposed.

Many archives, libraries, and collections are housed in pre-existing buildings, some having listed status and therefore changes to the building fabric may be difficult. As far as possible the building fabric should not allow or facilitate the easy scaling of the building that enables criminals to access the upper floor or the roof. However, downpipes, buttresses, and ledges often exist in older buildings and therefore measures to prevent or limit easy scaling should be considered. Appendix 4 outlines some of the anti-scaling devices that can help reduce the risk from climbing adversaries.

The roof itself should always be considered an area requiring protection, especially when easily accessible. Traditional slate or tiled roofs where they are affixed to battens are easy to move, gaining access to the spaces below. The use of timber, plywood sheeting, or expanded metal sheets will increase the robustness afforded. In older buildings permission may be required and the weight of materials used needs to be considered.

[1] Ensure LPS1175 compliant, SR3 or higher (https://www.redbooklive.com/page.jsp?id=488 )

TIP 10

When roof access leads straight into stores, special collections, or areas containing assets of significance then LPS1175 SR3 rated expanded metal sheets should be used.

6.4 External Doors

Doors and other portals allow ingress into the building and egress out of them. Because of this, they are frequently targeted as a point of entry for criminals, while emergency exits provide a speedy egress from the building.

Each venue should consider its own circumstances regarding the doors being used, sometimes they fall within a listed category, sometimes they will be made of glass, or panel doors that are easily bypassed. How robust the doors are should be based on the risk to assets, ease of access to assets, and whether there are any stipulations around the type of door being used.

Where the door has historical significance, permissible steps to improve the robustness should be taken which can include changing the locks so that they are BS 3621/8621 compliant, adding bolts to the rear face, or hinge bolts. However, no adjustments may be allowed and the closest you can get to making it more secure is by using door wedges/jammers (fire safety requirements should be considered) which are not sophisticated but more effective than having nothing or accepting the risk.

Where no restrictions exist, consider the categorisation of assets immediately behind the door. If ancillary, any type of door can be used if the ‘risk owner’ accepts the protection levels afforded. However, if the door leads to more secure spaces and valuable assets then the layered security principle should be adopted, and a more robust door considered to maximise the delay caused.

Where higher levels of protection are assessed as being needed then a door should be installed that meets those requirements such as LPS 1175 SR3. These higher security doorsets are built to specific designs and any changes to the design could nullify its rating, although if the change is minor the protection afforded may not be impacted, it is just that it cannot be certified as meeting SR3 standards.

A venue may have assets where a higher level of protection is appropriate but because of funding or other factors, it is not able to afford purpose-built security doors. It is still appropriate to attempt to increase the level of protection afforded as high as possible and this can be achieved by using the following:

Use a solid core timber door.

Consider fitting a 3mm steel plate on the inner face of the door leaf.

Add an additional mechanical locking device that conforms to BS 3621/8621 and is at least 5 levers.

Invert the hinges so they are not exposed to the attack (outer) side of the door.

Add two hinge bolts at 1/3 or 2/3rd height (or incorporated into the hinges themselves).

Consider bolts or drop bars as may be appropriate.

While the above cannot be tested each measure can play a part in slowing down an attack, which may be all that is needed to deter the attacker.

The shape and style of the doorway could be such that the fitting of a security grille or roller shutter is the preferred option. While from a security perspective, an LPS1175 SR3 feature would be desirable, any metal shutter or grille can slow down an attack and may have a deterrence effect, preventing an attack in the first place.

Emergency exits will be a feature of nearly all venues, especially when opening to the public. Their design is such that there is a need for a speedy egress when there is a fire, or the alarm is activated. The construction of emergency exits has changed over recent times with a greater number of metal ones now being installed. The composition of emergency exits out into public spaces should be able to be secured by another means (for example, bolts and mortice deadlocks) rather than just a standard push bar, (subject to approval, planner, fire, etc).

The use of magnetic locking devices on external exits should be avoided as they are designed to ‘Fail Safe’ which means they will automatically open on the activation of the fire alarm system (FAS). Criminals are aware of this and unless a secondary locking device exists the whole venue could become insecure by the intentional or false activation of the fire alarm.

The fitting of any locking devices or panic/emergency door bolts (containing glass/ceramic tubes) can be appropriate, as can the fitting of security-rated shutters/grilles, but approval must be sought if it is a fire exit. Equally, if an operational approach is taken to lock the doors once everybody has left the building then the organisational risk owners should document and approve it.

TIP 11

Ensure that any method used to secure emergency fire exits have been agreed by the Fire Department and Council Planners. Once agreement given confirm that the risk owners approve it.

Each door should be considered individually as the loss, harm, or damage to assets will vary greatly and some spaces may be viewed as ‘surrenderable’ due to the number of other layers between that point and critical assets.

Other external access points to consider include vents, hatches, cellars etc., and how these are secured needs to be considered based on the risk to assets, including the sewer system (especially in historical buildings). If accessing them brings somebody near a ‘protected space’ or critical assets, assess if additional physical security measures are needed.

6.5 External Windows

Windows traditionally consist of timber frames fitted into a wall or roof, with glass panes added to allow people inside to see out, light to enter buildings, and in some cases for environmental conditioning. The concept has not changed much, although the designs and materials used have become far more sophisticated, apart from the continued use of glass.

Glass[1] is not a secure material and is prone to accidental and intentional breakages. Externally, glass is used in windows, doors, skylights, and other areas where light enters buildings (including glazed curtain walls as outlined earlier). Criminals will use windows to enter a building, especially if they can see physical security enhancements to doors and other portals. There is also an increase in attacks through windows taking place above the ground floor where physical security enhancements have been made, including at historical and cultural venues.

Most safety glass conforms to either BS6206 or BS EN 12600 both of which use pendulum impact or drop height tests to measure performance. Toughened and laminated glass is normally measured against this standard.

EN356 standard is specifically for ‘security’ glazing and has eight categories of resistance against manual attack. This standard is supposed to simulate a human attacking the glazing. LPS 1270-approved glazing is tested by humans in the same way that LPS 1175 does against physical resistance to attack. EN356 is not as accurate a measure of attack resistance as LPS1270.

EN356 and P1A-P5A are tested as per BS6206 and BS EN 12600 and are viewed as low-level security glazing. P6B-P8B are tested using a mechanical hammer and axe blow and are viewed as the ‘Higher’ level of protection. LPS 1270 uses a range of tools as per LPS1175 and is rated between 1-8 based on the level of resistance (8 being the highest 20-minute work time within an attack duration of 60 minutes).

It should be noted that the more secure glazing is the heavier the weight and the greater the cost, which may be relevant in buildings where load bearing is an issue. Appendix 5 outlines the most common types of protective glazing used in buildings.

The protection of any window must be risk-based, the greater the risk/asset significance the more protection should be afforded. (See Appendix 6) There are also financial and operational considerations about what is used in the protection of windows, the level of protection will be based on the venue-specific circumstances that exist and the level of risk and vulnerabilities identified.

While the above relates to external windows it is equally as applicable to skylights and other glazed features on the building exterior.

6.6 Internal Physical Features

Just because the shell of the building is protected it does not mean that inner layers of security do not need to be applied. This is especially true when the archive, library or collection is in a building that is shared with others or where there is not full control.

A central reception desk where everybody reports is a great physical barrier as it forces users to engage with staff, who may then remember certain individuals especially if they do not fit an expected visitor profile. However staff need to be careful to avoid discrimination or making unfair pre-judgements, bearing in mind the stipulations of the Equality Act.

Another example of where physical and operational measures come together is the control of bags and other items used for carrying non-essential or banned items. The provision of lockers is an indirect risk reduction strategy as it lowers the likelihood of objects being stolen or illegal items being taken into the Search/Reading Room.

When the building is closed to the public and operational teams it can sometimes be easy to compartmentalise the spaces so that if somebody gained entry from outside the building, they would still have to bypass other physical barriers before they reached any of the critical assets. Therefore, by adopting a policy where doors are locked, and electronic locks are used helps create further delays before an aggressor reaches critical assets.

There should always be a clear delineation between public spaces and back-of-house areas. Physical security means of controlling who enters what areas should be introduced and can be as simple as locking all rooms where the public are not permitted, using a push button combination lock (PBCL), through to a more modern electronic access control system that provides an individual with permission to access certain areas.

With other internal and external stakeholders, an agreement should be reached as to how your specific area of responsibility can be locked down at night or when your space is closed operationally. There may be a difference in approach between general search / reading rooms and spaces designated for the use of special collections.

During the day there will be an increased use of the search/reading rooms, therefore, the physical layout of the room is important to ensure that areas of concealment are reduced and the positioning of tables and desks that staff have a clear and unobstructed view of the room. Ideally, there should be nobody with their backs to anybody invigilating or working in the space. The physical presence of a member of staff who has a clear line of sight (supported by CCTV) may be sufficient to deter a criminal act from taking place. (Of course the invigilator is also there to provide help, advice and guidance on handling of documents).

There is a need to consider other forms of attack that are not theft-driven, and this can include incidents of violence, protesters, or acts of terrorism. Irrespective of how unlikely these acts are they cannot be ruled out therefore, consideration should be made for evacuation or locking down certain areas to prevent physical ingress. The following should be considered; safe routes, are there predetermined shelter-in-place locations? How many people do they hold? Do they have escape routes if the attacker tries to gain entry?

All are sensible questions to ask and areas where professional help may be needed from the police through CTSA (Counter-terrorism Security Advisors) or DOCO (Designing Out Crime Officers) or other trusted security professionals with the knowledge and experience to assist. Advice is also available on ProtectUK, particularly the Publicly Accessible Location (PALs) guidance, concerning attack scenarios, lockdown, invacuation and evacuation procedures.[2]

6.7 Stores

Archives, libraries, and collections are stored for future retrieval, safekeeping, and protection from all threats. Collection stores can generally be split into two types, ‘general’ and more secure stores. This section will deal with the general storage practices while 6.8 will look at more secure storage.

The store or ‘stack’ can contain millions of items, many of which date back hundreds of years outlining so many aspects of life in bygone eras. While most will not have a specific financial value attached to them, they are all valuable and should be protected.

Doors leading into the stores should at least be constructed using:

Solid core timber door[3]

An additional mechanical locking device that conforms to BS 3621/8621 and is at least 5 levers.

Inverted hinges so they are not exposed on the attack (outer) side of the door.

Add two hinge bolts at 1/3 or 2/3rd height (or incorporated into the hinges themselves).

Where possible electronic ACS (Access Control Systems) should be used so that access control is managed, auditable, and restrictions on who enters can be applied. Where this is not possible other operational practices need to be considered.

Walls leading into the stores should be robust and provide sufficient resistance to further delay any attack and forced entry, this is also applicable to the roof.

Due to most archives and libraries containing flammable and combustible materials fire is one of the greatest risks that exists. As far as possible the store should be constructed using non-flammable materials and preferably materials that offer 4 hours of fire resistance, although any additional resistance is better than none.

The volume and nature of collections requiring storage will dictate the size of the store and the type of stacks being used.

Specific guidance can be found in standards BS 4971: 2017 Conservation and care of archive and library collections and BS EN 16893: 2018 Conservation of Cultural Heritage. An excellent reference document has also been produced by the British Library regarding the most effective use of shelving, outlining pros and cons associated with each type. As far as possible the most appropriate shelving/containers should be used to better protect and preserve the collections.[4]

Archival stores should not be used as a secondary ‘junk’ room due to space restrictions elsewhere, unnecessary non-archival materials, especially combustible ones, should be removed and stored elsewhere.

6.8 Secure Storage Facilities

A secure storage facility should be used where there are ‘Special Collections’ or items of significant financial or historical value. By their nature, these documents have an increased attractiveness to criminals, especially those from organised crime groups due to the increased financial rewards.

Unless a completely secure ‘bubble’ can be created no ‘secure store’ should be positioned against an outer wall where a ‘ram-raid’ type attack can be carried out. The location of the secure store should be known only by those who ‘need to know’ and access must be tightly controlled. Providing that accessibility is not an issue, elevation from the ground floor helps create a spatial barrier (additional delay) which must be bypassed before an attack starts.

As far as possible, purpose-built LPS 1175 C5/D10 rated doors should be used to restrict access into the secure store. The walls should be constructed using multiple-thickness brick, concrete, or suitable blockwork, single layers of brick/block should be avoided wherever possible due to their vulnerability to blunt force attacks. If necessary, the walls can be suitably reinforced using LPS 1175 C5/D10 modular walling systems or expanded metal sheets.

Where this cannot be achieved any practical means of enhancing the levels of protection should be considered and can include the securing of sheet metal to the inner/outer face of the store walls, shelve placement, non-highlighting of documents or even secondary security containers within the ‘secure store’ such as safes and vaults.[5] Any reference to a wall in a ‘secure store’ also means the floor and the ceiling. Fire preventative measures similar to those outlined in 6.7 above should be considered.

Access into the store should be restricted and if a programmable ACS is not available, key control measures should be introduced. This should include the provision that the keys never leave the premises and are secured within an appropriate safe/security container when not in use.

6.9 Exhibiting and Display Cases

There will be times when a venue will want to exhibit collections, it could be that they are on permanent display in a gallery, corridor, or highlighted space and as such away from the normal levels of security that are afforded in stores. It is important that the balance between outreach and asset protection is maintained so that unnecessary risks are not introduced.

When planning an exhibition consider what is needed to protect the assets and whether they are being placed at increased risk. Areas of concealment and darkened areas should be avoided so that invigilation is not made more difficult. Consider how items are secured onto walls or plinths and think about any potential safety issues, e.g. if a stone bust fell onto a child. Pictures should be secured using mirror plates and security screws, or other suitable locking devices.

Small removable exhibits should not be positioned close to exit doors[6] and while a frequent practice, rope delineation barriers will only prevent compliant visitors from approaching exhibits, with negligible effect on non-compliant individuals or groups.

Archival items will always be displayed within a protective enclosure such as a display case. In many older venues display cases are made of wood with float glass inserts. To this day these cases exist and while providing demarcation and preventing the handling of sensitive and fragile objects they are not suitable as a physical security barrier. Even previously provided guidance regarding types of glass, thickness etc. have been superseded because of the use of more sophisticated tools in the arsenal of the criminals. Older cases may also be prone to environmental problems such as off-gassing of non-archival sealants / paints.

If the older type of display case forms a part of the experience and aesthetics, then providing it does not contain high valued articles or those of historical significance it can continue to be used providing the risk, including any environmental risk, is accepted by the owner.

A modern security display case will provide increased protection against attack, but they can still be bypassed. The guidance[7] identifies the following:

As a minimum the glass should comply with BS5544 which is generally met by the use of 11.5mm five-ply laminated glass. (Acrylic/Perspex with a minimum thickness of 12mm is still shown as being acceptable.)[8]

The case is to be steel framed with flanged corners to hold the glass in place. These flanges should have at least 20mm overlap around the glass to prevent a levering attack on the corners of case.

Unglazed sides to the case will need to be of steel. MDF type materials are unsuitable.

The case is to be secured with high-standard locks. Generally, at least two locks should be fitted to each opening in the case. Ideally, locks should be concealed and protected from direct attack.

Lighting to be housed in a separate light box compartment secured by different locks to the main display section which will enable the lighting system to be maintained without opening the display section.

The case to be constructed to prevent access to the collection material via the light box compartment.

Similarly, if the case is built over a storage compartment this should be secured separately with the case constructed to prevent access to the collection material via the storage compartment.

The case must be robust and sturdy so that it cannot be readily moved if knocked.

Internally any shelving or display elements to be fitted to prevent collapse or movement if the case is knocked.

Ideally hinges should be concealed and thereby protected from direct attack.

The only difference with the above advice is brought about by the improved protective elements of glass and therefore the use of LPS 1270 security rating 6-8 or EN 356 P6B-P8B rated glass should be considered especially if the case contains high-valued items (financial, historical, global significance) or is at an increased risk of being attacked due to ideological, racial, political, or environmental reason. There is a potential cost implication and increased weight placed on the steel frame, but the likelihood of a successful attack is significantly reduced. Alarms can also be fitted to cases to enhance security further.